DragonFly, WRITTEN BY Jules Hull, Sep 19, 2019 · 10 min read

By mid morning on Wednesday 6th August, when a lot of investors and market participants would have been enjoying a much needed break by the seaside, Burford Capital, an AIM darling for half a decade, had lost over 70% of its value, c£1.7bln wiped out, in just a few hours of trading. At the heart of this destruction in shareholder value/repricing was a Muddy Waters report detailing issues around accounting, misleading disclosure and explicitly attacking the company’s weak corporate governance, with the headline grabbing “exposé” that the CEO and CFO were a married couple. The fact that many of the concerns had been expressed in prior sell side research added to the bewilderment around the share price reaction. Nonetheless the damage was done, the Pandora’s box of iffy corporate governance had been opened.

Even prior to Greta Thunberg’s rise to prominence, socially responsible investing had been growing at breakneck speed. Assets under management in European passive sustainable funds has more than doubled, to c$100bln (2018) from only $40bln in 2015. For many asset managers the E, standing for Environmental, and the S, standing for Social, are the headlining, asset grabbing elements of this theme. Companies have taken this on board too; for instance BIC, the maker of plastic lighters, pens, and disposable razors, has increased the word count in its ESG segment to a whopping 40k words, from only 14k a few years ago, presumably in an attempt to rebuff the reality that most of its products end up in landfill.

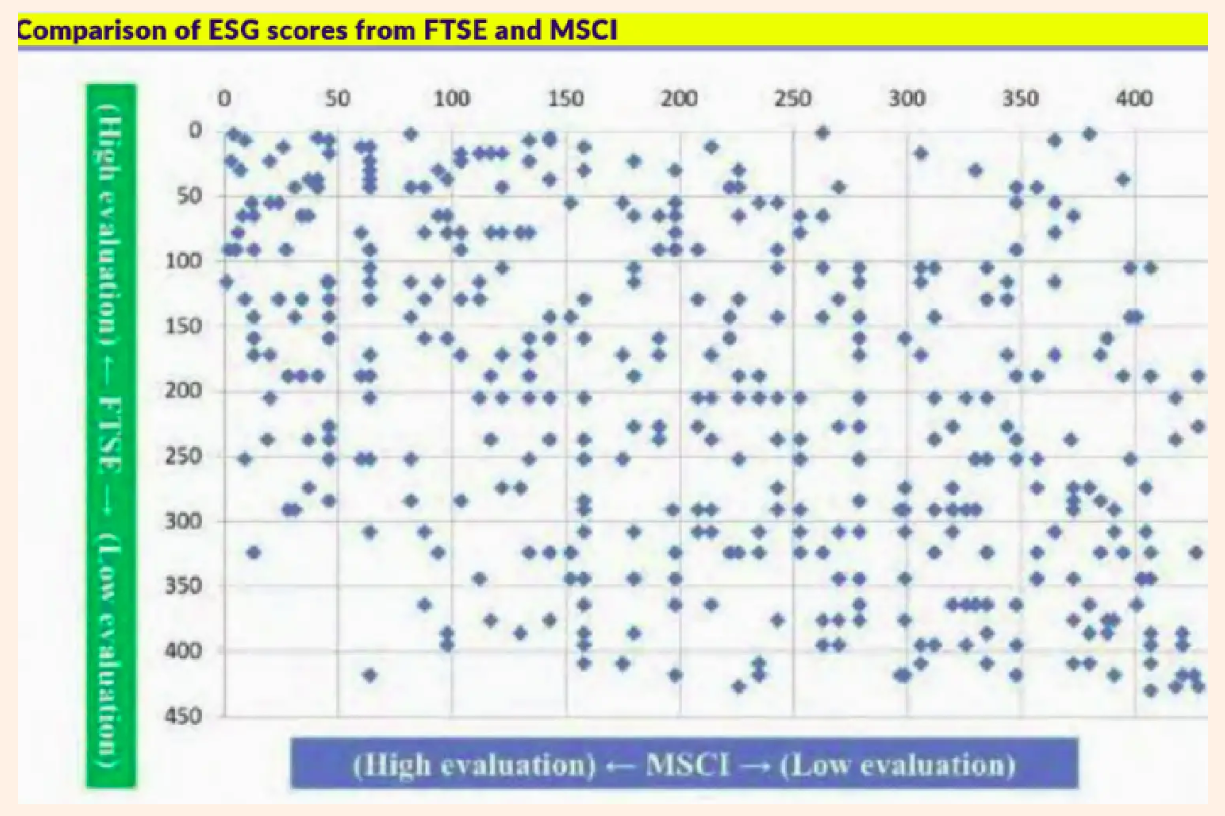

While there is much to applaud in rewarding those companies that are genuinely trying to make a difference, presumably with a lower long term cost of equity, this is a very contentious battleground (cf the fact Tesla is either bottom or top of some metrics on Environmental impact depending on your view on battery manufacture…and where you draw the line of direct impact). Nonetheless it has spawned a whole new branch of the industry specialising in ESG scoring, even if they can’t agree on anything.

In our eyes though the G, or Governance element of ESG, is the one area that can have more immediate impact on shareholder returns and is also (slightly) less contentious. Returning to Burford, most of the issues raised around disclosure of returns, opaque management pay, cosy linkages with key investors, an AIM listing and married management team would have been known about and were, to some degree, signed off by shareholders via voting. For Sports Direct, another UK plc where governance concerns make regular front pages, the spectre of mismanagement has manifested in losing an auditor and a struggle to find a replacement, due to reputational fears for the incoming audit firm. The lessons from both these examples is that bad governance, or the perception of bad governance, can have dramatic consequences for shareholders right here and now.

There is of course plenty of logic to investors being spooked by revelations around corporate governance. After all companies are run by human beings so the combination of poorly structured incentives, weak oversight and limited checks on power is very likely to manifest in bad decision making at best and something wholly less palatable at worst. Patisserie Valerie and Goals Soccer Centres being recent examples of the worst.

What is bad, or conversely, good governance and how can we measure it?

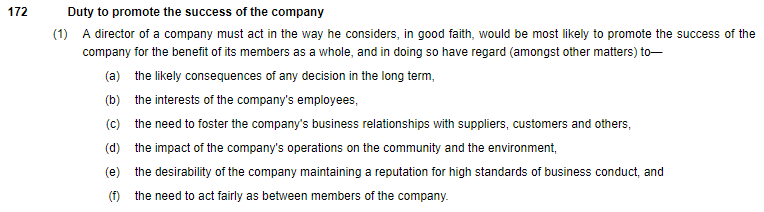

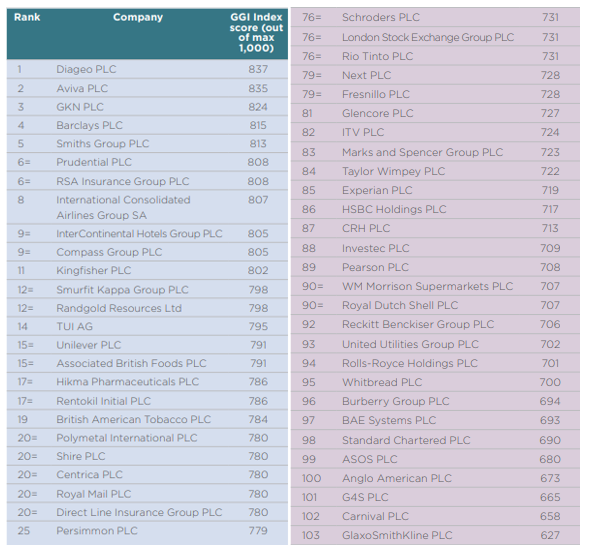

From 2015 to 2017 the Institute of Directors (IoD) ran a study across the FTSE 100 which was one of the most categorical attempts to score and assess corporate governance; Diageo and Aviva were at one end with GSK and Carnival at the other. Their guiding principle was section 172 of the Companies Act 2006 which reads accordingly:

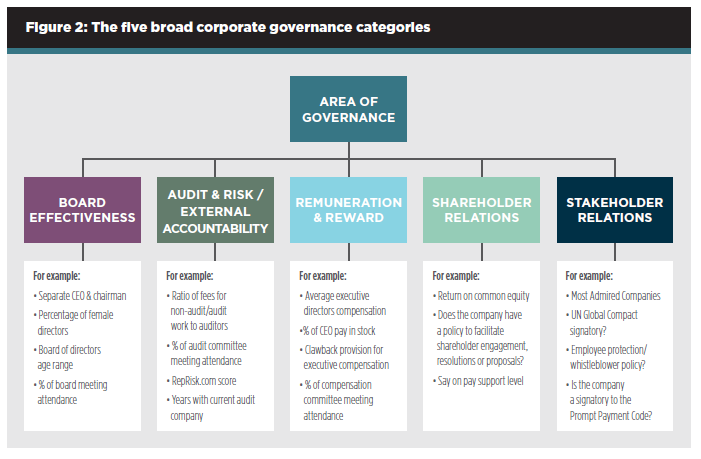

As a result the IoD scored 47 different indicators in 5 broad categories:

The first three categories make plenty of sense and are critical to the running of a company in the best possible way and aligning management with shareholders. For instance Board effectiveness contained measures like Chairman/CEO duality, percentage of non-execs, size of board, number of meetings, board attendance and board tenure. Audit accountability looked at % of independents on the audit committee, attendance of that committee, years with auditor, the ratio of non-audit to audit fees and number of audit meetings amongst other measure. The remuneration category, which we shall return to, looked at independent directors on the rem committee, size of the rem com, proportion of pay in stock, is a clawback included, ratio of total comp to market cap and a few other things.

The latter two categories — shareholder relations and stakeholders relations, are perhaps the most woolly as they included measures like share price volatility, RoE and whether the company was admired: all things that start to incorporate an element of circular feedback, are difficult to judge or are outside the board’s ultimate control. I.e. the share price has gone up a lot so the company becomes more admired and the stock less volatile so a better governance score, which might not actually reflect the reality. Or the company operates in a sector that has structurally low RoE due to the competitive dynamics of that industry. Even so there was a lot of common sense in the application; the top and bottom 25 companies are shown below.

Sadly adherence to good governance does not automatically produce a better share price performance. Indeed analysing the performance of the top and bottom 25 since March 2017 shows that only 9 of the top 25 outperformed the FTSE 100 to date, vs 8 for the bottom 25. Average returns of the top 25 has fared slightly better though at -5% vs -8% for the bottom.

So why worry about governance?

Trying to correlate governance with returns over the short term misses the real point. Bad governance is more analogous to damp in a wall, it builds up slowly, eating away at the structural integrity and, if caught early, needs cutting out, or else it can eventually bring the wall down.

As we have alluded the main way that governance becomes a problem is due to a combination of poor oversight, weak checks and most critically misaligned incentivisation, which tends to manifest in bad decision making and value destruction. From our perspective there are two aspects to misaligned incentives: firstly, the metrics used to assess management’s performance in running the company and secondly, via a direct linkage to the short term share price performance of a company’s stock.

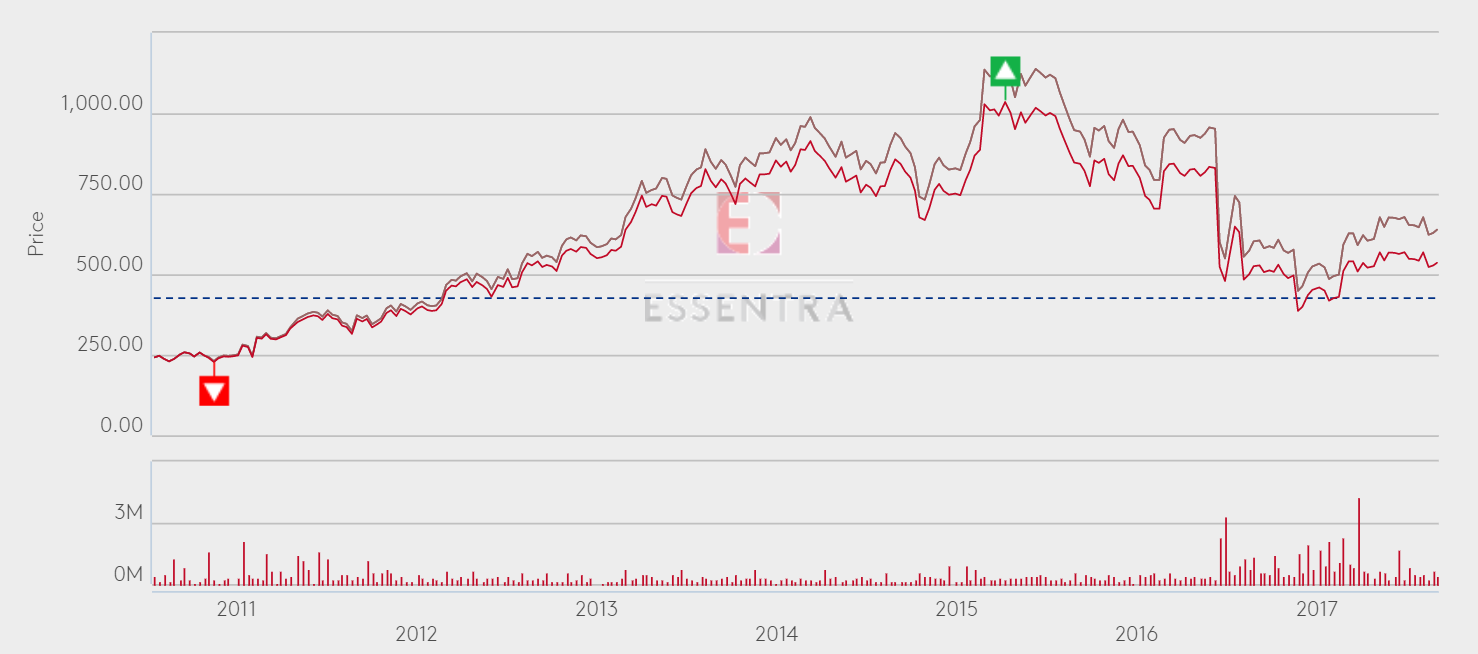

Take the recent example of Essentra, which was previously known as Filtrona. This was a business that, in the words of Colin Day, who was appointed as CEO in 2011 was “solid, steady, stable”. In the 2011 Annual Report he goes on to outline Vision 2015 and talks about “creating a virtuous financial circle” which revolved around growing the business rapidly via acquisition but still “focusing on cashflow”.

5 years later, in 2016, revenue had duly doubled to £1bln and adjusted EPS too. In response the shares had more than tripled in value and Colin Day, via a generous set of LTIPs had been paid in aggregate £15mln over 5 years. I vividly recall meeting Colin Day at that time and I was struck by the fact his aim was purely to double the size of the business by 2020. That was it; no mantra about fixing a customer problem, just doubling. You might think this is a glorious example of capitalism working in sync — hurrah for the system !— and everyone is basking in the glory of another doubling. Four years on however Essentra shares languish 60% below their peak, £125m has been written off with another £75m of one-off costs and Colin Day is no longer at the helm. So what went wrong?

A quick glance back at the way Essentra structured its incentives (and amazingly still does) explains a lot: the aim was to grow adjusted EPS and to deliver strong relative TSR, so much for that aforementioned “focus on cashflow”. As a result, during the four years from 2011 to 2015 the company spent just under £350m on acquisitions, it also clocked up almost £100m in acquisition fees and integration costs too. If you just looked at FCF or ROCE the former was flat over the period and ROCE had declined from 12.5% to 6.5%. The issue was that none of the costs of delivering the promised growth were included in management’s adjusted EPS. At the same time management were encouraged to promote the shares as actively as possible with LTIP schemes that rewarded based on TSR over 3 year periods. This is by no means the worst form of incentivisation we have encountered.

Indeed more recently schemes have emerged that reward management based on “shareholder value creation”. Owing their roots to private equity they effectively create an “all or nothing” opportunity for management rewarding a percentage of all value created above a threshold CAGR measured over a 3 year period. In practice this can mean life changing amounts (think winning Euromillions) vs nothing at all for say 11% vs 9% shareholder CAGR (assuming your threshold was 10%). This type of scheme was used for AA Plc’s IPO, and perhaps was a contributor to the extreme pressure that led to the CEO allegedly assaulting a colleague at an offsite.

What is the best way to incentivise a CEO?

Making management teams long term owners of capital is of course a sensible way of aligning them with shareholders but given the duration of the average CEO is barely 5 years, 1/6th of a savers potential post-retirement lifetime, there is a big mismatch in the aims of many large holders vs the aim of a CEO. The recent addition of clawbacks and minimum holdings goes some way to try and address this.

Perhaps the biggest problem with current standards is linking management rewards to short term (<5 years) share price behaviour. The problem is that new forms of trading mechanisms and market participants mean management can become overly focused on “beating the street” and delivering a constant string of upgrades, often by drawing attention to adjusted EBITDA, where those adjustments can sometimes beggar belief. In contrast we would argue that if management were to focus on delivering strong cashflow and re-allocating capital sensibly then the share price should look after itself.

This view is far from a revelation and has been central to Warren Buffet’s approach for some time. His focus is on the look-through earnings of his holdings and that being the key metric he truly values, this too is what management is really in control of:

Charlie and I let our marketable securities tell us by their operating results — not by their daily, or even yearly, price quotations — whether our investments are successful. The market may ignore business for a while, but it will eventually confirm it. Berkshire Hathaway Annual Report (1987)

Looking at the remuneration policy of Ryanair, a company that has rewritten Warren’s own rules that investing in an airline is how “billionaires become millionaires” is telling. Michael O’Leary has stewarded Ryanair for 20 years plus and is known for his astute capital allocation, generating a total return CAGR of 13.5% even after the recent falls in the share price. What is notable is that annual bonuses are capped at 100% of salary but “senior managers have rarely received 100% of their bonus entitlement, the average in recent years (when budgeted PAT has been achieved) is between 70% to 90%”, this is quite a contrast to other companies where targets seem to get set to be easily beaten, not to be so challenging that 100% is a rare event. Of that 100%, 50% based on profits and 50% on underlying business targets which “focus on strategic objectives such as traffic targets, ancillary revenue growth, cost control, customer service metrics, and operational performance (including punctuality)”. Ie the very metrics which dictate the success or failure of Ryanair as a business.

For long term incentives Ryanair has an option scheme which isn’t necessarily perfect however its goals are to “encourage management, through share options, to think and act like long term shareholders and prioritize shareholder returns. Options will only be exercisable where exceptional profit or share price targets have been achieved over a 5-year period from date of grant. Managers must remain in full time employment with the Group for a 5-year period from the grant date in order to exercise these options.” This means to truly benefit from an option scheme you need to be present for 10 years. No 3 years and run here…

A sad footnote

There is however a sad footnote to this which beggars the question: do institutional shareholders really want management focused on long term targets? It is no secret that the pressures from low cost passive investments have conversely led to even shorter term behaviour by many fund managers, desperate to remain ahead of the index every quarter. So in the 2019 Annual Report Ryanair have made the following statement:

The current share options plan, which was approved by shareholders at the 2013 AGM (“Options Plan 2013”), encouraged our people to think and act like long-term shareholders and prioritise sustainable returns. While this plan has been successful…it became clear that there is a need to put in place a more regular, formalized, long-term incentive arrangements for our senior managers…Under this new framework, senior managers may be eligible to receive regular annual awards, typically of whole shares rather than share options, with vesting based on performance against stretching three-year targets…. The performance conditions attached to LTIP 2019 awards are currently expected to be an equal weighting of three year EPS growth and three-year relative TSR performance against airline peers.

Whilst at least this is TSR vs peers, it does leave a rather worrying final thought: what hope do we have when even the best are succumbing?