Bloomberg/BusinessWeek, By Sabrina Willmer,

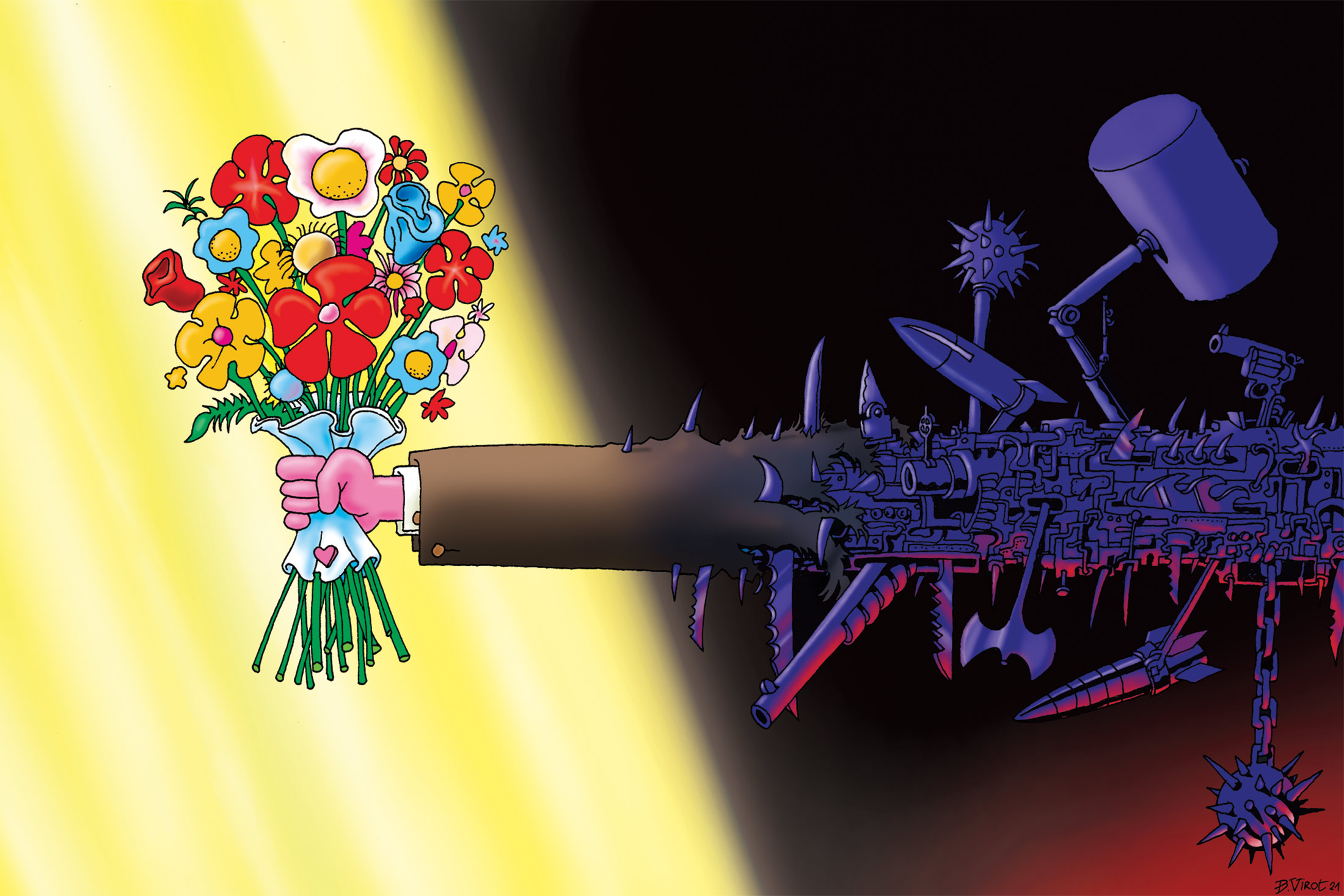

Private equity funds are touting investments that can help the environment and society, but the impact is hard to measure.

A record 132 “impact” funds have started this year, according to data from Preqin, which tracks the industry. The category has amassed $20 billion since 2015, data compiled by Bloomberg show. Impact funds often target investments in renewable energy, health care, affordable housing, or other socially important industries. More broadly, many clients want firms to consider ESG criteria, the industry shorthand for a company’ environmental, social, and governance practices.

“If there isn’t investor demand, they wouldn’t be doing it,” Bob Jacksha, chief investment officer for the New Mexico Educational Retirement Board, says of the industry’s efforts. “The skeptical part of me is: ‘Hey, this is a new marketing tool.’ To some extent it is.” But it could also be that “founders of companies simply believe in ESG,” he says.

Some of the biggest investors in private equity funds are pension plans whose beneficiaries are concerned about climate change and social justice. “Investors are going to want to more than hear it—they want to see it,” says Jefferies analyst Jerry O’Hara. The industry is trying to show that it’s listening.

In September, Carlyle Group Inc. and Blackstone Inc. joined with clients, including the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, to share and privately aggregate information related to emissions, diversity, and the treatment of employees across companies. The aim is to create standards and metrics that can track progress industrywide. (Bloomberg LP, the parent company of Bloomberg Businessweek, is a provider of ESG data to financial professionals.)

Detractors of private equity question whether an industry known for buying companies and then piling on debt, cutting costs, and cashing out in three to five years will leave those businesses better off. “People are doing normal leveraged buyouts, but they take a subset that are feel-good sectors and call that impact,” says Ludovic Phalippou, an economics professor at the University of Oxford’s Saïd Business School. “These investments would have been made anyway.” He says he doubts private equity can deliver on ESG promises because the industry is unwilling to sacrifice returns.

Funds are plowing ahead. KKR & Co. is marketing its second impact fund after wrapping up capital-raising for its first one last year at more than $1 billion. Apollo Global Management Inc. was on track as recently as July to lock in more than $500 million for its inaugural impact fund.

Both firms point to 12 years of responsible investing efforts, including ESG reporting from their portfolio companies. Apollo says it will incentivize executives to hit certain impact targets. It’s promised to link 2% of its cut of the fund’s profit to meeting those goals, but only after returns reach 8%, according to a marketing document. The firm is relying on part of its buyout track record to promote the fund.

One of the companies it highlighted as an example of doing well by doing good is Amsterdam-based Lumileds, which supplies energy-efficient LED lighting. Within a year of being bought in 2017, Lumileds took on debt to pay dividends, including $405 million to Apollo’s eighth flagship buyout fund, handing it 50% more than what it put into the deal, according to a quarterly report sent to clients.

Since then, Lumileds has fired almost 1,000 employees, about 11% of its 2018 workforce, its 2020 sustainability report shows. Moody’s Investors Service, which warned in May of a possible default, blamed the company’s debt-funded dividends in part for its current woes. “These are certain features that generally make the financial strategy of private equity ownership riskier than many publicly listed firms,” Swami Venkataraman, a senior vice president on Moody’s Investors Service’s ESG team says of the industry’s approach.

Lumileds carried a conservative debt load when it declared the dividend and only later faced unforeseen industry challenges that were exacerbated by the pandemic, Apollo spokeswoman Joanna Rose said in an emailed statement. “We are working closely with the management team to preserve the company, to return it to profitability and continue delivering best-in-class products,” she said.

At KKR money is already rolling in, though the effort is in its infancy. Its first do-good fund sold part of its stake in KnowBe4 Inc. and was on track to reap a fivefold return as of midyear. KnowBe4, which helps companies prevent phishing attacks by hackers, qualified as an impact investment, according to KKR, because its business model fits with sustainable development goals set by the United Nations.

KKR, mostly through its impact fund, took a dividend of about $16 million from Graduation Alliance, a company that helps high school dropouts graduate, just 16 months after buying the business. The payout wasn’t funded with debt, a KKR spokesperson says. KKR is using surveys to measure outcomes for graduates and is running a pilot program to link Graduation Alliance’s executive pay to retention and enrollment.

Given the various ways firms measure impact or ESG across their portfolios, investors and activists are pushing for more data. “There is an urgent need for greater transparency to avoid what we have now, where companies write a narrative with cherry-picked anecdotes,” says Alyssa Giachino, climate director of advocacy group Private Equity Stakeholder Project.

The Private Equity Stakeholder Project wants to see firms do more and has called on the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission to subject them to more stringent climate-risk disclosures. Companies including KKR, Blackstone, and Apollo have come under fire from the group for their investments in fossil fuels.

The American Investment Council, which represents the private equity industry, is lobbying against such requirements. It says that firms are already required to notify clients about any significant impact on their businesses and that the industry should be held to a different standard because it mostly deals with sophisticated investors. Private equity firms have cited their increased investment in renewables, efforts to make oil and gas holdings more responsible, and the critical role traditional players still have in meeting society’s energy needs.

As Carlyle sees it, oil and gas companies and other ESG laggards represent an investment opportunity. Megan Starr, who focuses on impact across the firm’s strategies, says such businesses can be bought at a cheaper price, improved on ESG measures, then sold for a tidy profit. “We have one of the strongest incentives to focus on improving assets from an ESG performance perspective,” she says.