Bloomberg, By Cam Simpson, Akshat Rathi, and Saijel Kishan,

MSCI, the largest ESG rating company, doesn’t even try to measure the impact of a corporation on the world. It’s all about whether the world might mess with the bottom line.

For more than two decades, MSCI Inc. was a bland Wall Street company that made its money by arranging stocks into indexes for other companies that sell investments. Looking for ways into Asian tech? MSCI has indexes by country, sector, and market capitalization. Thinking about the implications of demographic shifts? Try the Ageing Society Opportunities Index. MSCI’s clients turn these indexes into portfolios or financial products for investors worldwide. BlackRock Inc., the world’s biggest asset manager, with $10 trillion under management, is MSCI’s biggest customer.

Sales have historically been good, but no one was ever going to include MSCI itself in an index of sexy stocks. Then Henry Fernandez, the only chairman and chief executive officer MSCI has ever had, saw it was time for a change. In a presentation in February 2019 for the analysts who rate MSCI’s stock, he said the company’s data products, the source of its profits, were just “a means to an end.” The actual mission of the company, he said, “is to help global investors build better portfolios for a better world.”

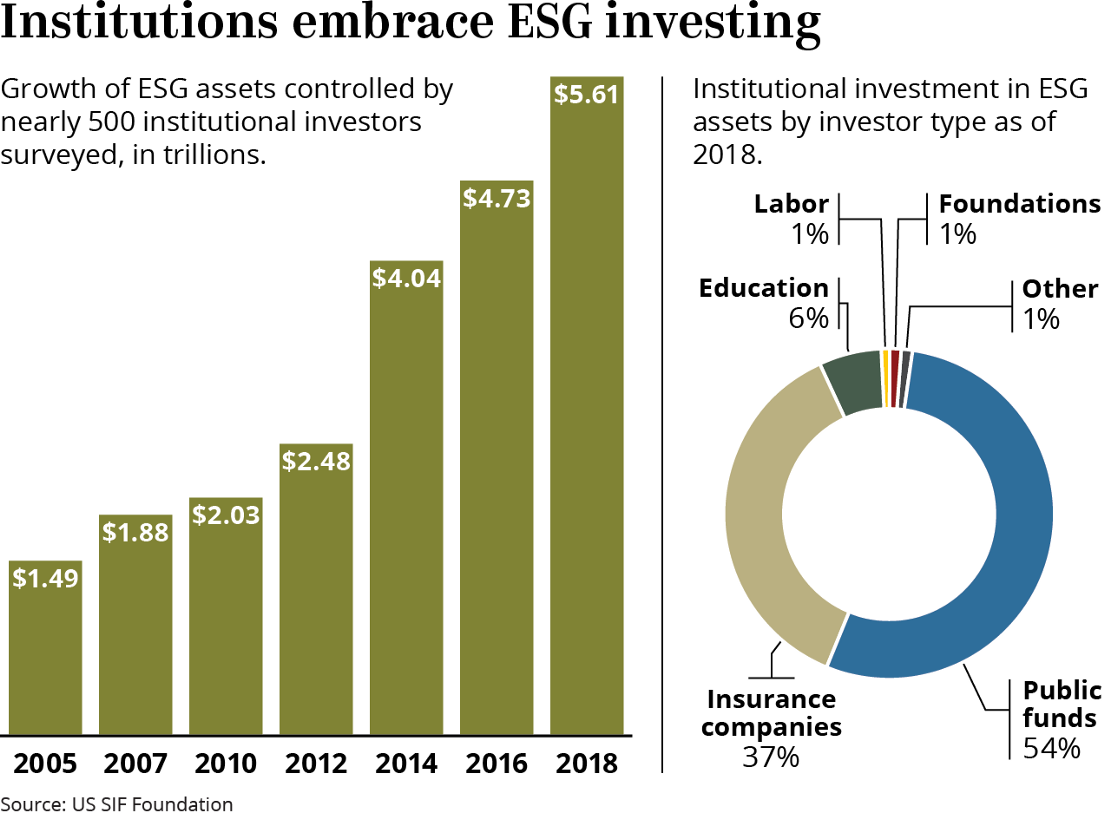

Fernandez was borrowing the language from an idealistic movement that originated with a couple of fringe money managers in the 1980s. Yesterday’s heterodoxy is today’s Wall Street sales cliché. Investment firms have been capturing trillions of dollars from retail investors, pension funds, and others with promises that the stocks and bonds of big companies can yield tidy returns while also helping to save the planet or make life better for its people. The sale of these investments is now the fastest-growing segment of the global financial-services industry, thanks to marketing built on dire warnings about the climate crisis, wide-scale social unrest, and the pandemic.

No single company is more critical to Wall Street’s new profit engine than MSCI, which dominates a foundational yet unregulated piece of the business: producing ratings on corporate “environmental, social, and governance” practices. BlackRock and other investment salesmen use these ESG ratings, as they’re called, to justify a “sustainable” label on stock and bond funds. For a significant number of investors, it’s a powerful attraction.

Yet there’s virtually no connection between MSCI’s “better world” marketing and its methodology. That’s because the ratings don’t measure a company’s impact on the Earth and society. In fact, they gauge the opposite: the potential impact of the world on the company and its shareholders. MSCI doesn’t dispute this characterization. It defends its methodology as the most financially relevant for the companies it rates.

This critical feature of the ESG system, which flips the very notion of sustainable investing on its head for many investors, can be seen repeatedly in thousands of pages of MSCI’s rating reports. Bloomberg Businessweek analyzed every ESG rating upgrade that MSCI awarded to companies in the S&P 500 from January 2020 through June of this year, as a record amount of cash flowed into ESG funds. In all, the review included 155 S&P 500 companies and their upgrades.

The most striking feature of the system is how rarely a company’s record on climate change seems to get in the way of its climb up the ESG ladder—or even to factor at all. McDonald’s Corp., one of the world’s largest beef purchasers, generated more greenhouse gas emissions in 2019 than Portugal or Hungary, because of the company’s supply chain. McDonald’s produced 54 million tons of emissions that year, an increase of about 7% in four years. Yet on April 23, MSCI gave McDonald’s a ratings upgrade, citing the company’s environmental practices. MSCI did this after dropping carbon emissions from any consideration in the calculation of McDonald’s rating. Why? Because MSCI determined that climate change neither poses a risk nor offers “opportunities” to the company’s bottom line.

McDonald’s

MSCI then recalculated McDonald’s environmental score to give it credit for mitigating “risks associated with packaging material and waste” relative to its peers. That included McDonald’s installation of recycling bins at an unspecified number of locations in France and the U.K.—countries where the company faces potential sanctions or regulations if it doesn’t recycle. In this assessment, as in all others, MSCI was looking only at whether environmental issues had the potential to harm the company. Any mitigation of risks to the planet was incidental. McDonald’s declined to comment on its ESG rating from MSCI.

This approach often yields a kind of doublespeak within the pages of a rating report. An upgrade based on a chemical company’s “water stress” score, for example, doesn’t involve measuring the company’s impact on the water supplies of the communities where it makes chemicals. Rather, it measures whether the communities have enough water to sustain their factories. This applies even if MSCI’s analysts find little evidence the company is trying to restrict discharges into local water systems.

Even when they’re not in opposition to the goal of a better world, it’s hard to see how the upgrade factors cited in the majority of MSCI’s reports contribute to that goal. In 51 upgrades, MSCI highlighted the adoption of policies involving ethics and corporate behavior—which includes bans on things that are already crimes, such as money laundering and bribery. Companies also got upgraded for employment practices such as conducting an annual employee survey that might reduce turnover (cited in 35 reports); adopting data protection policies, including at companies for which data or software is the entire business (23); and adopting board-of-director practices that are deemed to better protect shareholder value (25). MSCI cited these factors in 71% of the upgrades examined. Beneath an opaque system that investors believe is built to make a better world is one that instead sanctifies and rewards the most rudimentary business practices.

The True Colors of MSCI’s ESG Ratings

Criteria such as these explain why almost 90% of the stocks in the S&P 500 have wound up in ESG funds built with MSCI’s ratings. What does sustainable mean if it applies to almost every company in a representative sample of the U.S. economy?

One thing it’s meant for MSCI and its leader: a more than fourfold increase in its share price since the start of 2019, when Fernandez introduced his “better world” rebranding. Through his own holdings, that’s likely made him the first billionaire created by the ESG business.

MSCI is hardly alone in enabling Wall Street’s hottest new sales craze. About 160 providers, including the three biggest corporate-credit rating agencies and Bloomberg LP, the parent company of Bloomberg Businessweek, compete to sell sustainability ratings and data to money managers. (Bloomberg LP also has a partnership with MSCI to create ESG and other indexes for fixed-income investments.) But MSCI’s dominance of ESG is overwhelming. Bloomberg Intelligence estimates that 60% of all the money retail investors have plowed into sustainable or ESG funds globally has gone into ones built on MSCI’s ratings. (Fernandez told Businessweek he thought the real number was higher.) UBS Group AG, the Swiss investment bank, found MSCI earns almost 40¢ out of every dollar the investment industry spends on such data, far more than any rival.

Scoring companies on ESG criteria is nothing like rating them for creditworthiness. Different credit rating agencies almost always give the same ratings, because their assessments are based on identical financial data and they’re all measuring exactly the same thing: the risk that a company will default on its debts. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission regulates credit raters.

MSCI and its competitors in ESG rating, by contrast, often disagree with one another, sometimes wildly. That’s because each ESG rating provider uses its own proprietary system, algorithms, metrics, definitions, and sources of nonfinancial information, most of which aren’t transparent and rely heavily on self-reporting by the companies they rate. No regulator examines the methodology or the results.

Nonetheless, MSCI borrows the grading scale, and the aura of credibility, of standardized credit ratings. MSCI converts its numerical scores for E, S, and G into overall ratings such as AAA, BBB, and the like. It’s the only one of the major ESG raters to use those grades.

In MSCI’s system, companies are measured not against universal standards but against their industry peers. And the starting proposition is that an average company in each peer group is worthy of a BBB rating. MSCI doesn’t use the term “investment grade,” but that’s what BBB has meant for decades on Wall Street. By default, an average fossil fuel producer, utility company, automaker, used-car dealer, bank, retailer, chemical manufacturer, or arms maker earns that grade from MSCI. When a peer group swings, or MSCI changes its methodologies, companies can get upgraded for doing nothing other than staying the same. Businessweek found half of the 155 companies that got upgrades did so in significant part because of changes to the way MSCI calculated scores, not because of any change in the companies’ behavior.

Robert Zevin has a unique perspective on how Wall Street has flipped sustainable investing on its head. He’s one of two money managers credited with formalizing the practice in the 1980s, when it was known as socially responsible investing, or SRI. “It’s not just Wall Street,” Zevin says, “it’s capitalism. It always finds some way to repackage an idea so it’s profitable and mass-producible, and that’s going to be hard to overcome.”

Zevin stumbled into the creation of ethical investing. In the late ’60s, he was managing family money while also teaching economics at Columbia and running an anti-Vietnam War movement called Resist. While fundraising for the cause, Zevin found that some wealthy individuals were shocked to discover that a peace activist was also a money manager. They started asking him to manage their wealth in ways that didn’t conflict with their values. He later did similar work at U.S. Trust Co. of Boston.

Robert Schwartz was the other asset manager credited with formalizing ethical investing. He was the manager of investments for pension and welfare funds at Amalgamated Bank, which had been established by a labor union for garment workers. Schwartz discovered the union’s funds were being invested in companies with anti-union policies. He reversed that and built an ethical-investing business at the bank. Later he brought clients with him to Bache & Co. and Shearson, where he was a broker.

Fernandez, like other ESG leaders, traces the business to the SRI movement. But there’s a chasm between the two approaches, particularly when it comes to climate issues. No matter how big a company’s greenhouse gas emissions are, they might not even count in MSCI’s ESG rating. As long as regulations aimed at mitigating climate change pose no threat to the company’s bottom line, MSCI deems emissions irrelevant.

Hence the decision to eliminate emissions from consideration of McDonald’s, and the upgrade that came as they rose. “This issue does not present significant risks or opportunities to the company and with the assigned weight of 0% does not contribute to the overall ESG rating,” MSCI’s report said. Far more relevant to McDonald’s bottom line, MSCI determined, was whether governments might further regulate its packaging. So those European recycling bins and the announcement of a policy to reduce plastic wrap gave McDonald’s a 7 out of 10 on its underlying “E” score.

This wasn’t unusual. Almost half of the 155 companies that got MSCI upgrades never took the basic step of fully disclosing their greenhouse gas emissions. Only one of the 155 upgrades examined by Businessweek cited an actual cut in emissions as a key factor. As the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development warned in a 2020 report, this means investors who rely on “E” scores and ratings, even high-ranking ones, can unwittingly increase the carbon footprint of their pensions or other investments.

Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell

Although it’s hardly a household name, D.R. Horton Inc. builds more homes in the U.S. than any other company. Globally the construction industry is one of the biggest drivers of greenhouse gas emissions, as are its finished products. Together they accounted for almost 40% of global energy-related emissions in 2019, according to a report by the United Nations Environment Programme and the Global Alliance for Buildings & Construction. That year, the report found, the “sector moved away and not towards the Paris Agreement” goal on cutting emissions.

D.R. Horton, which has a market capitalization of $38 billion, doesn’t disclose any of its emissions, making it impossible to know exactly how big its contribution to climate change is. But the number of homes it built with the industry’s green certification standards dropped to 3.4% last year, from an already modest 3.8% in 2019. MSCI upgraded the homebuilder anyway in March, giving it a BBB rating and citing a recalculation of D.R. Horton’s “corporate behavior” score for policies on business ethics and corruption. The upgrade was MSCI’s second of D.R. Horton in a year. About 10 weeks later, the homebuilder was added to the largest sustainable investment fund in the world, BlackRock’s iShares ESG Aware MSCI USA ETF. As the name suggests, it’s built on data licensed from MSCI. (D.R. Horton is no longer in the fund, but it hasn’t been downgraded.)

JPMorgan Chase

Another company in the fund is JPMorgan Chase & Co., which since the announcement of the Paris Agreement at the end of 2015 has underwritten more bonds for fossil fuel companies—and earned more fees from them—than any other bank in the world. MSCI upgraded it in December 2020 to BBB. The rating report cited the bank’s self-described green credentials: the publication of its first “climate report”; a committee it had formed on “green projects”; and the underwriting of $14.6 billion in so-called green bonds in 2019. It didn’t mention the bank’s fossil fuel bonds, which dwarfed green bonds in dollar volume. (That said, the trend in green bonds is going up while the trend in fossil fuel bonds is going down.)

On May 21, MSCI gave a rare two-level upgrade to discount retailer Dollar General Corp.—from a junk B rating to BBB. Although the rating report noted that 89% of the company’s revenue comes from selling “carbon intensive products,” MSCI’s analysts cited three other factors in Dollar General’s double jump: data protection (it appointed a chief information officer); the announcement of a policy to limit products made with certain chemicals; and what MSCI described as internal ethics safeguards.

All of this makes perfect sense within the rules of the ESG game. MSCI’s focus is profitability. That’s why consideration of greenhouse gas emissions is a significant factor for regulated utilities but not a factor at all in the score of McDonald’s. Utilities will be seriously exposed to higher costs if stricter emissions regulations come into effect. McDonald’s, JPMorgan, and Dollar General won’t.

Even sophisticated investors can be forgiven for not knowing what’s going on inside the ratings used to build their ESG funds. MSCI’s detailed rating reports are available only to its financial-industry clients. The sellers of ESG funds don’t add much clarity. On the main page of its website for individual investors, BlackRock advertises iShares ESG Aware MSCI USA as offering exposure to “U.S. stocks with favorable environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practices.” It doesn’t tell anyone what “favorable practices” actually means.

Fernandez concedes ordinary investors piling into such funds have no idea that his ratings, and ESG overall, gauge the risk the world poses to a company, not the other way around. “No, they for sure don’t understand that,” he said in an interview in November on the sidelines of the COP26 climate change summit in Glasgow, Scotland. “I would even say many portfolio managers don’t totally grasp that. Remember, they get paid. They’re fiduciaries, you know. They’re not as concerned about the risk to the world.”

A Bloomberg Intelligence analysis earlier this year showed that BlackRock’s ESG Aware holds a portfolio that closely tracks both the S&P 500 and BlackRock’s own top-selling S&P 500 fund, with two notable exceptions: The ESG fund has a “sustainable” label thanks to MSCI, and it’s more heavily weighted in 12 fossil fuel stocks than the actual S&P 500. Asked for comment, BlackRock said that the fund is not designed to offer investors the top ESG-scoring companies and that it shouldn’t be compared to the S&P 500.

One other critical difference between the two BlackRock funds: Fees for ESG Aware are five times those for the S&P 500 fund. The ESG fund, now holding $24.8 billion, has grown by about $1 billion a month.

Not everyone on Wall Street is comfortable with the profits being made by giving investors the impression that they’re contributing to the fight against climate change. Tariq Fancy, BlackRock’s former chief investment officer for sustainable investing, initiated a one-man campaign this year against “green” financial products. “In essence, Wall Street is greenwashing the economic system and, in the process, creating a deadly distraction. I should know; I was at the heart of it,” he declared in an essay for USA Today. Fancy and others say the emphasis on ESG has delayed and displaced urgent action needed to tackle the climate crisis and other issues, including the widening chasm between the rich and poor.

Fernandez has said he views ESG investing as a tool for preempting change as much as one for bringing it about. When he was on a marketing blitz last year to promote what he called the urgent need for the world to more fully adopt ESG investing, Fernandez got on CNBC’s Squawk on the Street, a kind of investment sports show for who’s up and who’s down on Wall Street. “By the way,” he told the hosts, “we’re doing this to protect capitalism. Otherwise, government intervention is going to come, socialist ideas are going to come.”

He went further in his interview at COP26, an interview MSCI solicited as it promoted ESG and a new climate-related data product. “It is 100% a defense of the free-enterprise, capitalistic system and has nothing to do with, you know, socialism or zealousness or any of that,” he said.

Fernandez started his Wall Street career at Morgan Stanley. There he persuaded the company’s executives to let him take over what he’s described as a “cost center”—the division that produced indexes, especially in international stocks. He started making money rather than losing it, and the bosses let him reinvest profits in the business. Fernandez spun it off and brought the company public in 2007.

MSCI got into what would become the ESG business through the $1.55 billion acquisition of a company called RiskMetrics, which sold data tools to help asset managers account for risk in their portfolios. In the process, Fernandez got two other businesses RiskMetrics had recently acquired.

One, KLD Research & Analytics Inc., was started by a cadre of socially responsible investing pioneers to examine environmental and social factors in companies listed in the S&P 500. The other, Innovest Strategic Value Advisors Inc., was developing an early forerunner of the ESG ratings business. “We were trying to change the DNA of financial markets to help change the world,” says Matthew Kiernan, founder of Innovest.

A culture clash simmered between new employees who were motivated by progressive causes and the MSCI employees who were devoted to creating products for money managers focused on profits. After MSCI laid off some of the old guard from KLD and shifted work to Mumbai, where lower costs enabled it to produce ESG-related data on a larger scale, tensions flared.

In 2011 an MSCI team was invited to give a presentation in Boston about their business to a group of professionals in socially responsible investing, recalls Matt Moscardi, a former MSCI analyst who spent almost a decade at the company. Things got heated. “They started asking us about the layoffs, shifting some of our business to India, and yelling at us for destroying socially responsible investing by turning it into one giant model for massive asset managers to use,” Moscardi says.

Fernandez calls many early ESG advocates extremists and says he pushed against their views inside the company. “I said, ‘No, our job is to turn ESG into the mainstream of investing, not to create so much friction, and so much controversy, that it goes to the periphery.’”

Within MSCI, some dismissed the ESG team as a less-than-lucrative sideline. The skeptics included Baer Pettit, the company’s president. “I’ve got to be honest,” Pettit told analysts in the same February 2019 call that Fernandez used to roll out his better-world theme. “It was not obvious to me five years or seven years ago that this would be the growth we have in this area. … But this is a great example of getting out ahead of the investment process, understanding the trends, and then being able to monetize them.”

In the same quarter in 2019 when he rebranded MSCI, Fernandez increased his holdings in its shares by 25%, his biggest boost since right after the company went public. With more than 2 million shares, he’s the company’s ninth-largest shareholder, below a list of big institutional investors. He reached billionaire status shortly after the opening bell rang on the New York Stock Exchange on the morning of June 17.

Fernandez was at COP26 both celebrating ESG investors—“You know for sure they’re gonna help the world get better, 100%”—and marketing a new product, the MSCI Net-Zero Tracker, which estimates direct and indirect emissions from 9,300 companies and checks whether their climate plans are aligned with global goals. Other ESG ratings providers offer similar products. It seems unlikely they will have an impact on the emissions of those companies, but in the sustainable-investing business, the more important factor might be whether ordinary investors think they will. —With Donal Griffin