Wired, Environment

As humans squander the Earth’s resources and throw away unwanted goods, meet the companies and communities offering ways of transforming waste back into reusable products

Every year, the world adds 11.2 billion tonnes of solid waste to our combined rubbish pile, according to UN figures – the decaying organic parts of which contribute five per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions. We need to find a way to reduce waste, and the answer could be moving to a circular economy, which seeks to design out wastage by making use of byproducts and reusing materials. “The circular economy is an excellent way to deal with many of the major crises that we are facing,” says Anne Velenturf, a circular economy researcher at the University of Leeds. “Producing stuff takes a lot of energy, and if we make better use of our products then we also save much of the carbon embodied in them.”

Novo Nordisk, Luca Locatelli

Novo Nordisk

Half of the world’s insulin comes from this factory in Kalundborg, Denmark, and its production relies on vast fermentation tanks full of yeast broth. Manufacturer Novo Nordisk passes its spent yeast slurry to Kalundborg Bioenergi to make biogas. “Any leftovers, you can put on the fields as fertiliser,” says Kalundborg Bioenergi CEO Erik Lundsgaard. The plant produces enough gas each year to power 5,000 households, but much of it goes back to running the factory.

AeroFarms, Luca Locatelli

AeroFarms

AeroFarms grows kale and lettuce in stacks in an old steel mill warehouse in Newark, New Jersey, planting seeds into cloth made from recycled plastic bottles and misting seedlings from the bottom up to save 95 per cent of water over field farming. Precision LED lighting uses only spectra relevant to plants to avoid wasting energy. But smart farming can only go so far: we bin a third of the food that we produce, some 1.3 billion tonnes a year, according to the UN. “Reducing production and consumption can limit the damage done to the environment,” says Velenturf.

AMARG, Luca Locatelli

AMARG

The Boneyard is home to around 4,200 aircraft parked across 11 square kilometres at a Tucson, Arizona air force base. But the 309th Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Group (AMARG), as it’s formally known, isn’t a junkyard – it’s a preservation facility. The planes are washed, drained of oil and fuel, and sealed from the elements, with the dry climate limiting corrosion and allowing parts to be reused and metal to be recycled. Each year, 300 planes are added with about the same number processed, several dozen of which are refitted and returned to the sky.

Prato, Luca Locatelli

Prato

The city of Prato, Italy, has been recycling wool at an industrial scale for two hundred years, and it’s paid off: the $2 billion (£1.5bn) industry employs 40,000 people. Garments are hand-sorted – unfashionable colours are set aside until trendy again – and shredded like paper. Globally, 100 million tonnes of textiles are trashed annually, with just one per cent recycled – of that, 15 per cent happens in Prato. Britons are among the worst for fashion waste, says Velenturf. “We buy double that of our European neighbours,” she says. “The average garment gets worn just ten times.”

Entocycle, Luca Locatelli

Entocycle

Half of the world’s habitable land is used for agriculture, with food production causing a quarter of greenhouse gas emissions and livestock numbers outweighing wild mammals 15 to one – we need to eat something else. Entocycle has a suggestion: insects. In this breeding room, the impact of different light spectrums on the creatures is tested. “They address another huge issue the planet is facing, which is food waste,” says Jude Bliss, head of marketing at Entocycle. “The black soldier fly larvae feed on food – pretty much any dead organic matter – that would otherwise be thrown away.”

Amager Bakke, Luca Locatelli

Amager Bakke

Amager Bakke is normally seen from the outside – even the Queen of Denmark gets to admire this waste-to-energy plant from her window. Located in the centre of Copenhagen, it was designed by architect Bjarke Ingels as a public space, with a ski slope and hiking trails on the roof (handy, as Denmark has no mountains). The plant burns 70 tonnes of waste an hour in two furnaces that reach 1,000°C, powering generators and warming local homes. The ensuing flue gases are cleaned via a series of filters, with nitrogen oxide further broken down into non-toxic nitrogen and water.

ORF Genetics, Luca Locatelli

ORF Genetics

This greenhouse, set in the Reykjanes lava fields in Iceland, is growing 130,000 bioengineered barley plants – but they aren’t destined for making bread or beer. Instead, all of this carefully grown vegetation is harvested for a plant-based replica of a human and animal protein called epidermal growth factor (EGF) – a highly prized ingredient used in anti-ageing skincare products. ORF Genetics powers the greenhouse with sustainable energy from the nearby Svartsengi geothermal power station, giving the year-round planting a negative CO2 footprint.

CLEARAS, Luca Locatelli

CLEARAS

Almost 80 per cent of wastewater is discarded into waterways, where its high levels of nutrients spark algae blooms that can damage ecosystems. In the US alone, more than 14,000 water bodies are considered low quality. CLEARAS uses algae as the solution to this, mixing it in a bioreactor with wastewater to consume phosphorus, ammonia and other materials. This leaves behind clean, oxygenated water and dried-out algae that is reused or sold for industrial use. The Roberts, Wisconsin, facility treats 820,000 litres per day, producing 180kg of algae biomaterial.

Hellisheidi Power Station, Luca Locatelli

Hellisheidi Power Station

Atop the Hengill volcano, Hellisheiði Power Station is Iceland’s largest geothermal plant, producing 303MW of energy and 650 litres of hot water every second. Over 100 wells, thousands of metres deep, capture steam from magma-heated groundwater to power seven turbines, while 300°C fluid is used to heat freshwater sent to Reykjavik via a 26km pipeline. Any hydrogen sulphide and CO2 is reinjected into the ground; minerals from the steam are used industrially.

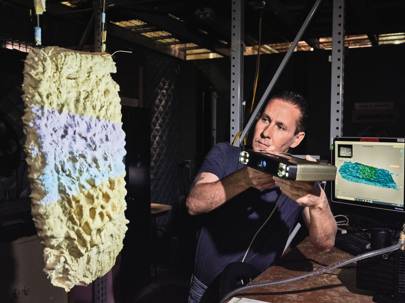

Ecovative Design, Luca Locatelli

Ecovative Design

Each year, 174kg of packaging waste is created per person, according to EU statistics – a figure that’s steadily increasing as our online shopping rises. Ecovative grows an alternative to packaging materials such as polystyrene and plastic or foam padding – by cultivating mushrooms. Agricultural waste, such as cotton hulls, can be used as feed for fungal mycelium. As this mycelium develops and breaks down the waste, its shape can be moulded to specific products and shapes. The used packaging, unlike the typical non-recyclable kind, can be composted at home. But Velenturf warns that, in general, “letting nature do the work for us” can have unexpected costs, for example in water use. “The only way to have a chance of becoming sustainable is by reducing average consumption per person,” she says.